"Bariolage "是一個法語單詞,指的是一種快速換弦的弓法,通常是在開弦和 "停弦 "之間,即手指向下的弦。這種產生快速音符的效果被廣泛用於各種音樂中,從巴赫到新音樂小提琴等等。成功演奏雙音階樂曲的關鍵之一是掌握各種跨弦的技巧,然後知道何時運用每種技巧。一個好的開始是學習兩種最基本的跨弦技術,然後學習如何將它們應用於快速換弦。

換弦,從肩部開始的大肌肉運動

簡單地說:在不同的琴弦上演奏需要不同的手臂角度,而從一根琴弦到另一根琴弦的變化涉及到角度的改變。例如,在小提琴的G弦上演奏時,手臂和肘部是相當高的。轉到D弦時,手臂和肘部下降到較低的位置(從肩關節處鉸接),彈A弦時再次下降,彈E弦時再次下降。了解彈奏每根弦時手臂和肘部的正確角度,以及彈奏雙停的EA、ED、DG和中提琴的GC弦時的角度是很重要的。當用手在兩根弦之間切換時,雙停的角度會非常有用。

在一定程度上,用較大的肌肉來換弦,用單獨的弓子來換弦是可能的,但是一旦到了非常快的速度,手臂就會開始像一隻慌亂的雞的狂躁的翅膀。這就是為什麼弦樂手還需要掌握如何使用手部較小的肌肉進行換弦(見下一節)。但重要的是要記住,大肌肉在兩個方面起著重要的作用:首先,你需要準確地設置和調整手臂的這些較大的角度來促進弦的交叉。其次,當雙線演奏還涉及到滑音或兩根以上的弦時,大肌肉的作用往往比小肌肉更好。

換弦,腕部的小肌肉運動

在兩根弦之間快速切換往往需要使用手部的小肌肉運動,從手腕處開始移動。如果你以前從來沒有這樣做過,你的第一步可能只是找到這些肌肉並加強你的大腦激活它們的能力。這裡有一個方法:用左手握住你的右手腕,用你的右手上下揮動,不要移動你手臂的任何其他部分來這樣做。接下來,用你的手順時針打圈,從手腕開始移動手,但不移動手臂的任何其他部位。

移到小提琴上:首先將弓子放在A弦上。用上述同樣的動作,把你的手翻起來,把弓子搖到D弦上。再把它翻下來,搖回A弦。用手的這種翻轉動作來回搖動。你可以試著用你的左手握住弓子的手腕,以確保你在弦間搖動時沒有移動你手臂的任何其他部分。一開始可能會覺得這個動作很馬虎,你的弓子可能會側著落到琴桿上。在開始的時候,允許有這種馬虎的感覺,只是為了熟悉這個動作。然後,隨著你對這個動作的熟悉,你可以把手指放得更鬆一些,看看你能不能在演奏的過程中,把弓子的角度保持得很直。

接下來,試著用小弓子在開闊的A弦和開闊的D弦之間進行切換:在下弦演奏下弓,在上弦演奏上弓–在這個例子中,D弦演奏下弓,A弦演奏上弓。你可以用你的前臂做一些水平運動來做上弓和下弓,但是換弦的動作完全來自手腕。

如何將換弦的技巧應用於特定的巴里歐拉琴段。三個例子

1. "魔鬼的夢"

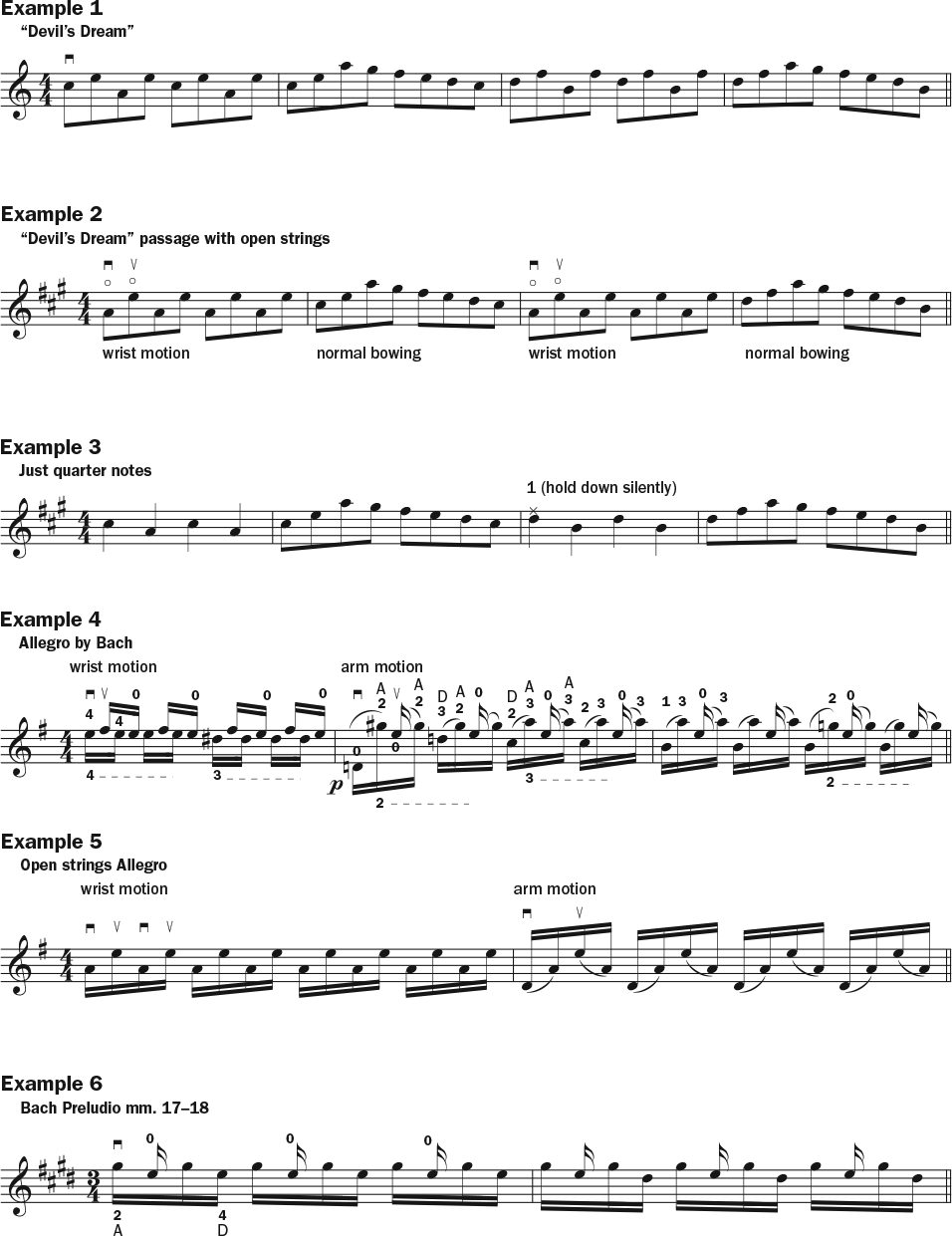

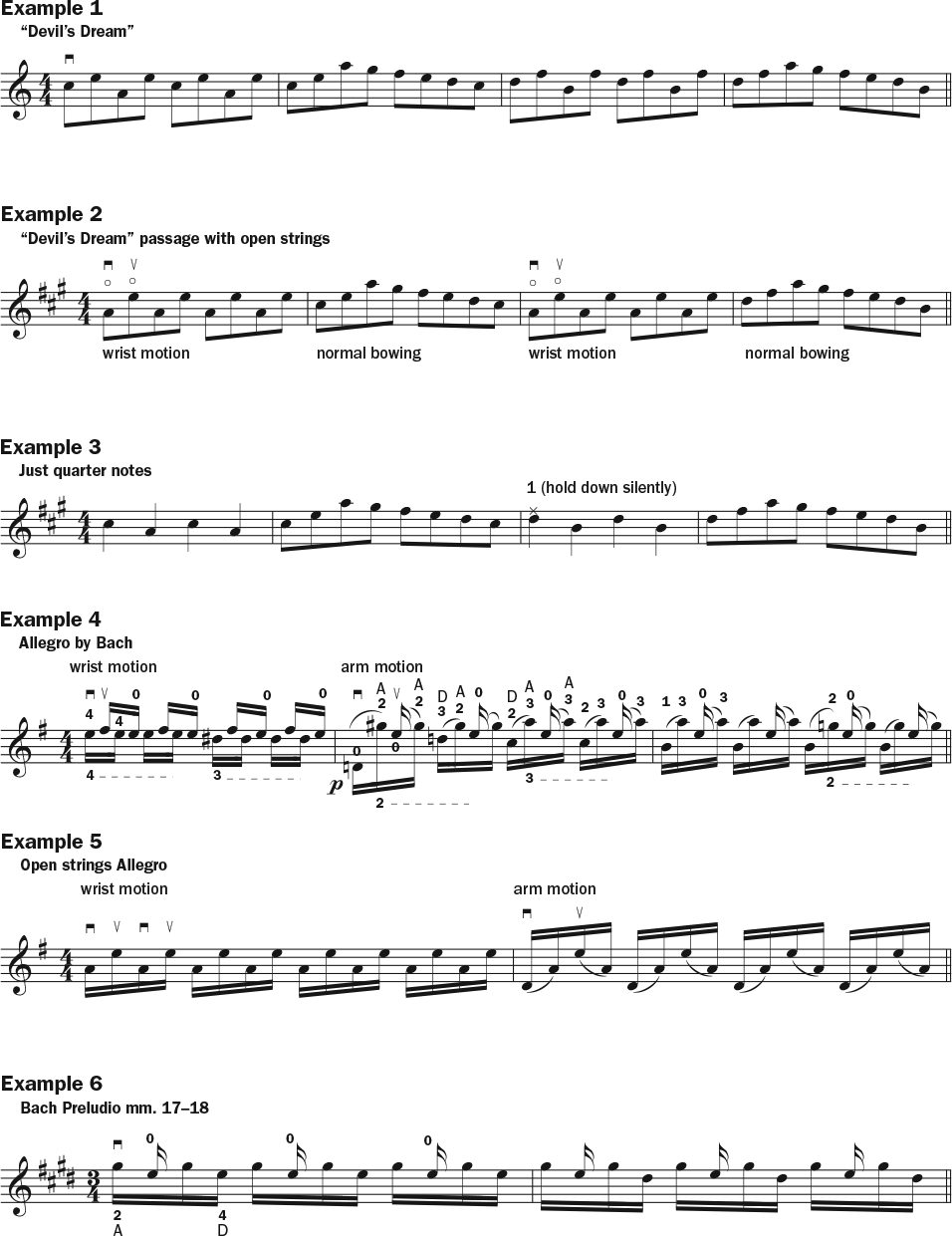

例1(如下),來自小提琴曲 "魔鬼的夢",兩根相鄰的弦之間用不同的弓子進行了交叉。

琴弦的交叉主要是通過手腕的圓周運動來實現的,在低處的琴弦上做下弓,在高處的琴弦上做上弓。練習時,像往常一樣演奏,但當你到了有交叉弦的樂段時,要演奏開放弦(例2)。關於左手的注意:在交替的弦上演奏固定的音符時,不要抬起你的手指。為了使你的左手保持平靜,你可以試著把低弦上的音符練成四分音符(例3)。即使在做雙音符的時候,也要繼續用這種方式來彈奏。

2. 巴赫的快板

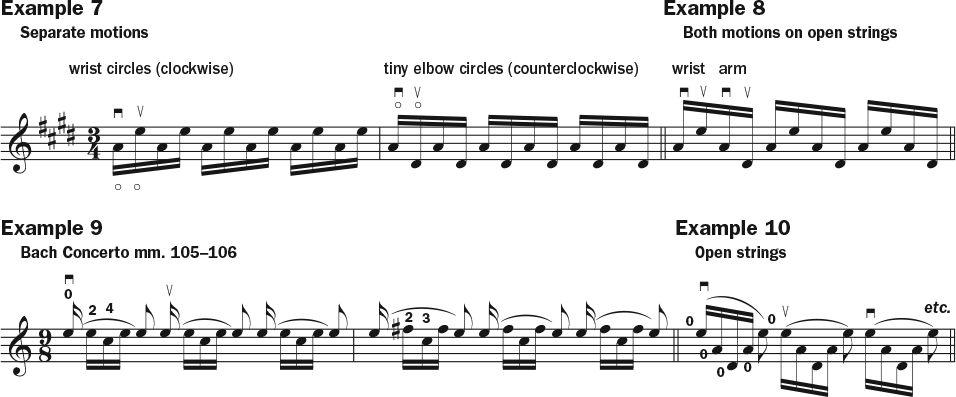

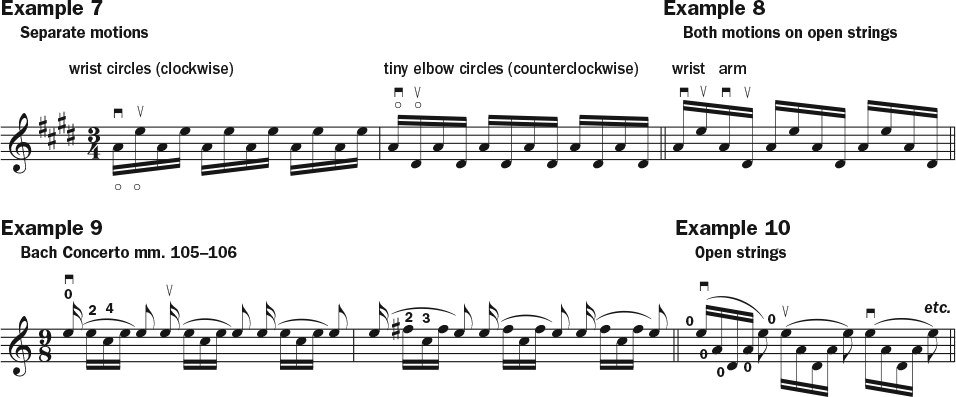

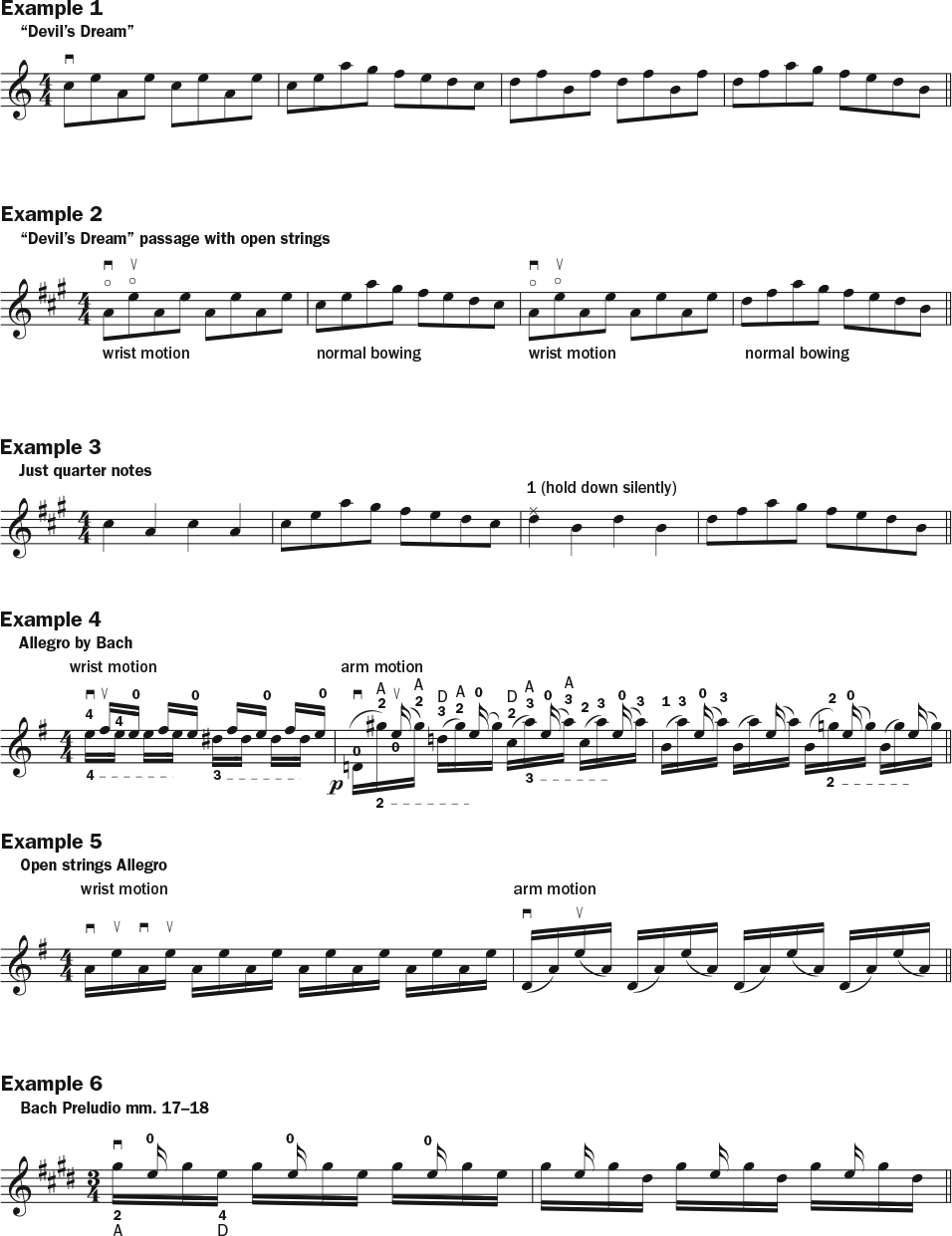

巴赫的《快板》是鈴木小提琴學校第八冊中的第四首作品,它提供了很多雙音練習。它的一部分(5-15毫米)包含了上面描述的基本的雙弦撥動,然而在第16毫米(例4),一切都改變了,增加了雙音滑音,一直持續到第19毫米。學生們經常試圖繼續使用手腕的動作(通常是新發現的)來演奏這一段,但是手腕的動作在這裡導致了不均勻的音符。在這裡,我們必須改用手臂的動作。為了停止手腕的運動,想像在你的手腕上打上石膏,同時使用所有較大的手臂運動。首先用開放的弦進行練習(例5):用手腕的弓子做單獨的弓子AEAE;然後改成用手臂的弓子做滑音DA EA DA EA。在開放的弦上練習滑音,直到手臂的動作從肩上完全流暢,音符聽起來完全均勻。它可以幫助強調最低和最高的音符。

順便提一下,當這段音樂在第20小節進入四個滑音的時候,動作仍然主要來自手臂,有一些非常微妙的手腕動作來移動到最低弦。

3. 巴赫E大調第三帕蒂塔中的前奏曲,供小提琴獨奏使用

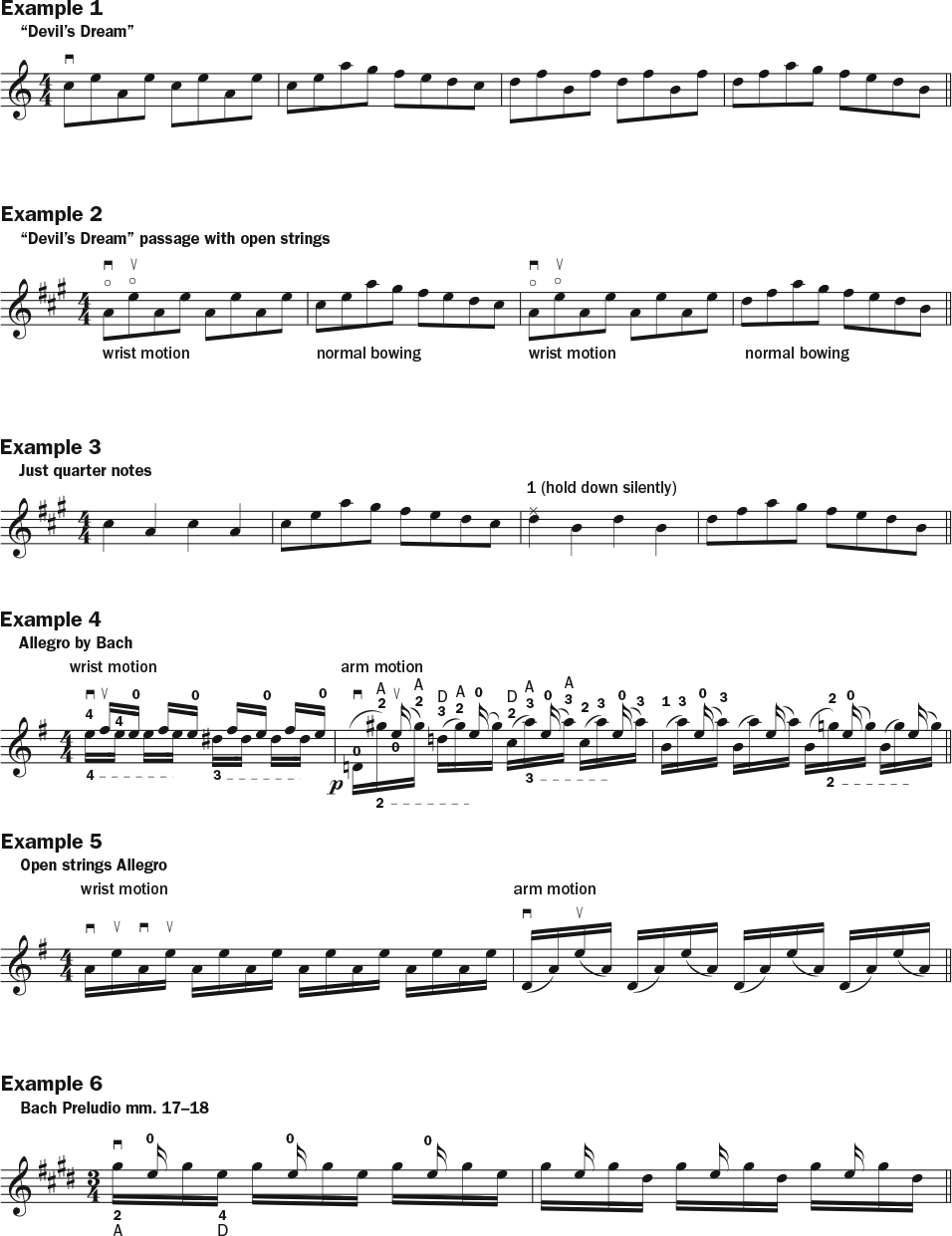

巴赫的六首小提琴奏鳴曲和帕蒂塔中的最後一首的前奏,也許包含了小提琴曲目中最流行的雙弦樂的例子。這個樂章包含了大量的雙弦撥動,但當巴赫在其中加入第三根弦時,事情就變得棘手了(例6)。 (這一段出現在第17-28毫米,然後在第67-78毫米再次出現)。在這裡,演奏者必須連續在三根弦之間,使用不同的弓子。從技術上講,在A和E之間的兩根弦上,必須使用手腕的動作,然後使用修改過的手臂動作,從A到D,再回到A。因此,這是兩種運動之間的不斷交替,在開始時非常棘手。

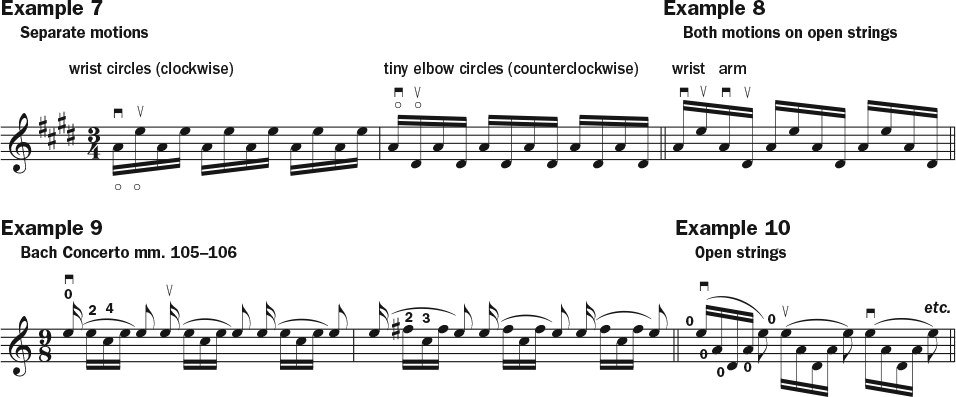

開始時,要把這兩個不同的動作分開(例7)。 A-E-A-E來自手和手腕;A-D-A-D來自手臂和肩膀。 (把這個動作看成是從 "肘部 "抬起來達到D,或者是肘部的小圓圈,可能在心理上會有幫助)。在開放弦上,把這些動作放在一起:手腕-手臂-手腕-手臂(或手腕-肘部-手腕-肘部)。手臂必須來迴旋轉,從EA級的手腕交叉到D級,以抓住低音。在所有這些音符中,手將保持運動狀態(例8)。當這種感覺很舒服時,再加上左手的手指。

音樂就是思想著的聲音。

Music is the sound of thinking.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Bariolage” is a French word for a bowing technique that involves rapid changing of strings, often between open strings and “stopped” strings—that is, strings with the fingers down. The effect, which produces a rapid flurry of notes, is used in a great variety of music, from Bach to bluegrass fiddle and beyond. One of the keys to success in playing bariolage passages is to master the various techniques for crossing strings—and then to know when to apply each technique. A good place to start is to work on two of the most basic techniques for crossing strings, then learning how to apply them to bariolage.

Crossing Strings: Large-Muscle Motion from the Shoulder

To put it simply: playing on different strings requires different angles of the arm, and changing from one string to another involves changing that angle. For example, to play on the violin’s G string, the arm and elbow are quite high. Moving to the D string, the arm and elbow drop lower (hinging from the shoulder joint), dropping again for the A string and again for the E string. It’s important to know the proper arm and elbow angle for playing each of the strings, as well as for the double-stop EA, ED, DG, and, on the viola, GC strings. The double-stop angle can be very useful when toggling between two strings with the hand.

It is possible, to a degree, to use the larger muscles to change strings for bariolage passages with separate bows, but once one gets to a very rapid speed, the arm begins to look like the manic wing of a flustered chicken. That’s why a string player also needs to master how to use the smaller muscles of the hand for string-crossings (see next section).

But it’s important to remember that the large muscles play an important role in two respects: first, you’ll need to accurately set and adjust these larger angles of the arm to facilitate string-crossings. And second, the larger muscles often work better than the smaller ones in cases when the bariolage also involves slurs or more than two strings.

Crossing Strings: Small-Muscle Motion from the Wrist

Toggling rapidly between two strings often requires using the small-muscle motions of the hand, moving from the wrist. If you’ve never done this before, your first step may be simply finding those muscles and strengthening your brain’s ability to activate them. Here’s one way to do that: holding your right wrist with your left hand, wave up and down with your right hand, not moving any other part of your arm to do so. Next, make clockwise circles with your hand, moving the hand from the wrist but not moving any other parts of your arm.

Moving to the violin: first rest the bow on the A string. Using the same motion as above, flip up your hand to rock the bow to the D string. Flip it back down to rock back to the A. Rock back and forth, using that flipping motion in the hand. You can try holding your bow wrist with your left hand, to make sure you are not moving any other part of your arm as you rock between the strings.

This may feel like a sloppy motion at first, and your bow might fall sideways onto the stick. In the beginning, allow for that sloppiness, just to get familiar with the motion. Then, as you get better at it, loosen your fingers more and see if you can angle the stick to stay upright as you rock from string to string.

Next, try toggling between the open A and open D using small bows: play down bow on the lower string and up bow on the upper string—in this case, down bow on D, up bow on A. Now send this motion out into your hand, using those clockwise circles, until you are not moving anything but your hand, from your wrist, to cross strings. You can use some horizontal motion from your forearm for the up and down bows, but the string-crossing motion comes completely from the wrist.

How to Apply String-Crossing Techniques to Specific Bariolage Passages: Three Examples

1. “Devil’s Dream”

In Example 1 (below), from the fiddle tune “Devil’s Dream,” the bariolage occurs between two adjacent strings, using separate bows.

String crossings are achieved primarily with circular hand motion from the wrist, going down bow on the lower strings and up on the higher strings. Practice by playing it as usual, but when you get to the measures with bariolage, play open strings (Ex. 2).

A note about the left hand: don’t lift your fingers for the fixed notes played on the alternate strings. To keep your left hand calm, try practicing the notes on the lower strings as quarter notes (Ex. 3). Continue to finger this way, even while doing the bariolage.

2. Allegro by Bach

The Bach Allegro that appears as the fourth piece in the Suzuki Violin School Book 8 provides a lot of practice for bariolage. A portion of it (mm. 5–15) contains the basic two-string toggling described above, however everything changes at m. 16 (Ex. 4), with the addition of two-note slurs that last through m. 19.

Students very often try to continue to employ the (often newfound) wrist motion to this passage, but wrist motion here results in unevenly executed notes. Here, one must change to an arm motion. To stop the motion in the wrist, imagine having a cast on your wrist while using all larger arm motions.

Start by practicing this with open strings (Ex. 5): bowing from the wrist for the separate bows AEAE; then change to bowing from the arm for slurring DA EA DA EA. Practice the slurs on open strings until the arm movement is completely smooth from the shoulder and the notes sound completely even. It can help to accent the lowest and highest notes.

Incidentally, when this passage goes into four slurred notes at m. 20, the motion remains mostly from the arm, with some very subtle wrist motion for movement to the lowest string.

3. Preludio from Bach Partita No. 3 in E major for solo violin

The introductory movement in the last of J.S. Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin contains perhaps the most popular examples of bariolage in the violin repertoire. The movement contains plenty of two-string toggling, but things get trickier when Bach adds a third string to the mix (Ex. 6). (This passage occurs in mm. 17–28, then again in mm. 67–78).

Here the player must go between three strings consecutively, using separate bows. Technically, one must use the wrist motion for the upper two strings, between the A and the E, then use a modified arm motion to rock down from A to D and back. So it is a constant alternation between the two kinds of motions—very tricky in the beginning.

Start by separating the two different motions (Ex. 7): A-E-A-E from the hand and wrist; A-D-A-D from the arm and shoulder. (It may be helpful mentally to think of this as lifting from the “elbow” to reach the D, or tiny elbow circles.)

On open strings, put these motions together: wrist-arm-wrist-arm (or wrist-elbow-wrist-elbow). The arm must swivel back and forth, from the EA level for the wrist crossing to the D level to catch the lower note. The hand will remain in motion for all of these notes (Ex. 8). When this feels comfortable, add in the left-hand fingers.

音樂就是思想著的聲音。

Music is the sound of thinking.